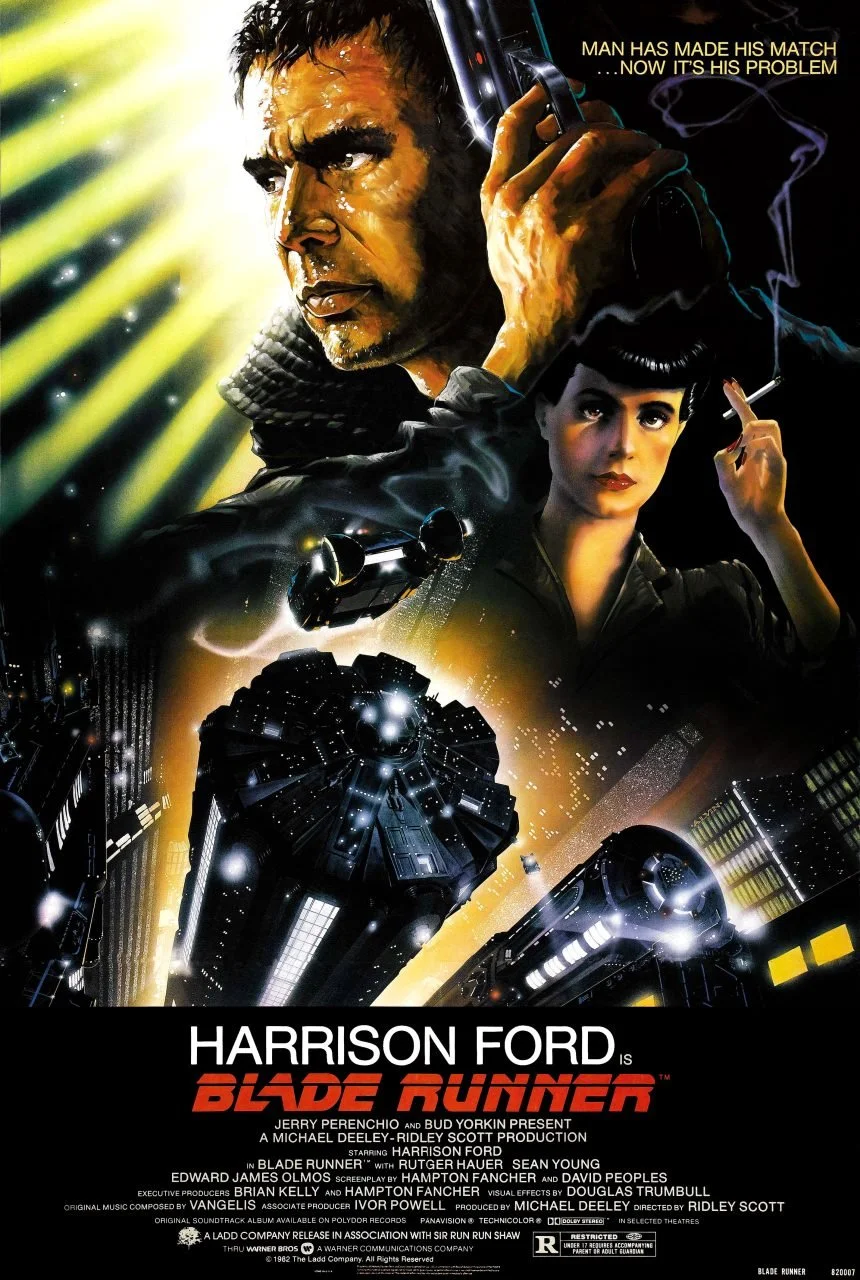

Blade Runner (1982, rev. 1992, 2007)

Back in 1982, director Ridley Scott dropped the audience into the then-future world of 2019 Los Angeles. It’s a seedy environment of continual darkness, fog, and urban sprawl. In this sci-fi noir, Rick Decker (Harrison Ford) is a retired blade runner brought back into the business after self-imposed retirement. A blade runner is a specialized detective whose job it is to track down fugitive replicants, which are bio-engineered humanoids. These are not robots, but they’re also not considered fully human due to their synthetic creation and lack of emotional maturity. Will Decker maintain his humanity during this ruthless pursuit, or has life in this dystopia already stripped him of it? Furthermore, there are deeper puzzles to solve, especially in 1992 and 2007 cuts.

1982 was a special year for science fiction films. In addition to Blade Runner, the year saw the release of E.T., The Thing, and Star Trek II; The Wrath of Khan, among others. Likely due to the crowded field and possible audience surprise at the film being not a typical heroic Harrison Ford picture of the time, the film was a box office disappointment. It made just 1.5 times its production budget, and this not including advertising, one can feel Scott’s and the studio’s hurt. Contemporarily, it’s still not a mainstream hit, but it’s developed such a cult following that the studio released a sequel years later. Moreover, Blade Runner’s aesthetic and mood influenced more popular science fiction films since it’s release than nearly any other property. This is why it’s good to see what makes Blade Runner still a thing.

Even years later, the visuals are still a wonder to observe. The combination of design and in-camera effects put the viewer in a world that is both tangible and strange. For those who have grown up on a diet of CGI, this is all physical and camera trickery. For the cityscape, the team utilized models and matte paintings, but the world is real enough that you can feel you can just drop in and shuffle amongst the crowded representation of the future. Just think of the time needed for the multipass exposures that helped give the film it’s unique neon-lit against darkness lighting. It gave the audience a different idea of what science fiction could be from the Star Wars and Star Trek properties.

But who are the characters that we’re following in this update of noir cinema? Dekker is the typical film noir detective: burnt-out, possibly alcoholic, and with no future. Really, he’s not much of a hero. Throughout the film he barely makes it out of his scraps, and when he does, there’s nothing triumphant. It’s not surprising that audience interest fell of the film when word got out that Ford was not playing another Indiana Jones or Han Solo. However, I think it’s interesting that Ford took the risk of playing the protagonist role so differently from his previous pulp characters. One could say he was reaching back to his brief role as an army officer in Apocalypse Now. Some say the disinterested attitude was due his dissatisfaction on the set, but it matched the character he was supposed to portray.

The star of the film is Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer). Despite being artificial, he’s the most sympathetic character, even after some his brutal actions. Despite being created as a type of superman, he displays the most human qualities during his quest with his fellow replicants. This is often done without words; though, his dialogue is memorable as well. The femme fatale Rachel (Sean Young) is probably the weakest of the main characters. Still, her stilted manner and speaking could be considered to be a positive attribute to add to the mystery of who she is revealed to be. Other acting props are for the weirdness of Gaff, the cold detachment of Tyrell, and the playful quirkiness of Pris.

What is most memorable about Blade Runner is the music. The production could’ve gone with traditional orchestration. Vangelis instead composed a melancholy, jazzy synth score. This perfectly sets the mood for the future setting, while paying tribute to the tropes of film noir. In fact, in addition to the synthesizers, the score utilized a saxophonist for the popular “Love Theme.” In addition, you can hear bits of Asian and Middle-Eastern tinges throughout the film, showcasing the multiethnic atmosphere of 2019 Los Angeles. Does it date the film being produced in the eighties? To a certain extent, yes. However, one should distinguish between quality and mediocre synthesizer work. Quality work brings a since of wonder, charm, or menace depending on the emotional mood of the film. It gives added texture to remind a person that this film is from a never to be repeated era. Vangelis could be considered to be one of the masters to bring on that nostalgia.

Dull, lethargic, and plotless has been some of the criticisms leveled against Blade Runner. Looking at the film from a certain point of view, these thoughts could have some merit. This is not an action film, at least not in the way that the term has evolved in the modern area. It’s a work that emphasizes mood and atmosphere rather than focusing on getting the hero from point a to point b. Some will balk at this type of cinema. That’s their right. There’s a reason why the film has been re-released in multiple cuts over the years beyond the Ridley Scott revisions. But they shouldn’t discount the impact that the film has. It’s never going to be widely beloved like many of the blockbusters of the time. Even some more critically and popularly derided fare of the time like The Thing have seem to risen to more public consciousness than Blade Runner. Still, Blade Runner welcomes at least a first view for the uninitiated. It’s through this type of relatively grounded science fiction that we see bits of the future running before us rather than soaring into space.

NRW link: https://newretrowave.com/2021/12/06/blade-runner-1982/